- Published on

iOS > Android: View Life Cycle

*DRAFT*

- Authors

In this post, I’m going to compare the life cycle hooks in iOS and Android, and discuss at a high level why iOS’s system is superior to Android’s. In general, iOS provides hooks that match the life cycle of the view, which creates an easy and intuitive system, and successfully hides system level concerns from the developer. On the other hand, Android's hooks follow the state of the controller, which conflates the life cycle of the view with the state of the controller, breaking the fundamental abstraction of MVC. This terrible design creates a confusing and quirky system, and exposes system level complexity to the developer.

MVC refresher

To establish terminology, I'll quickly discuss Model-View-Controller, the design paradigm favored by both platforms. MVC seeks to reduce the complexity of user interfaces by separating concerns into models, views, and controllers. Models hold the data. Views are the representation of the data on screen, and should contain minimal logic. Controllers manage the views and their life cycle, and coordinate with models and the rest of the app. Since controllers are in the middle of everything, they are usually significantly more complicated than views.

The View Life Cycle

When a view is about to appear on screen, the app needs to perform the following tasks:

- Create the view and load into memory

- Lay out and measure the elements of the view

- Render the view on screen

And when the view should leave the screen:

- Hide the view

- Release memory

These tasks represent the major stages in a view's life cycle, and a developer might want to take action at some or all of these stages. For instance, a developer may wish to persist the state of the UI when a view is going off screen. To support these actions, each platform has provided a number of hooks in their controllers.

The Life Cycle Hooks

Apple's most common methods are:

- ViewDidLoad

- ViewWillAppear

- ViewDidAppear

- ViewWillDisappear

- ViewDidDisappear

As you can see from names like 'viewDid' and 'viewWill,' the iOS hooks are focused on the state of the view. The hooks do not make any assertions about the state of the controller, or the larger state of the app. Apple has successfully separated the concerns of the view from the concerns of the rest of the app in their life cycle hooks.

This separation, along with aptly-named hooks, creates an intuitive system. For instance, it's obvious that viewWillAppear will get called when the view is about to appear. It is also clear that viewDidAppear will get called after the view has been rendered on screen, and after any associated system level tasks have been completed. In general, I find the iOS hooks clearly named, and thoughtfully laid out. I will note that the developer is still responsible for learning what happens at a system level before each hook. For instance, views are not measured in viewDidLoad, so any requests for a dimension will return 0, which can be a source of frustration for new developers. But I find these details easy to look up.

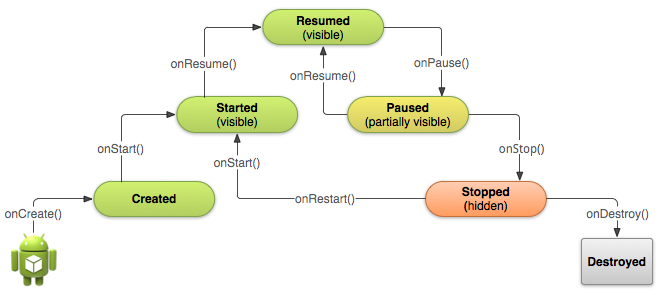

Here are the equivalent Android docs.

In contrast to iOS, Android's hooks get called when the controller is about to change state, not the view. The states, like "paused" and "resumed," are controller states. In fact, Android's hooks make no mention of the view at all, and as we will see, only have a peripheral connection to the life cycle of the view. This abstraction is incorrect and adds enormous complexity to Android's system.

This incorrect abstraction is apparent in the names of Android's hooks, which are confusing and ambiguous. For instance, what does it mean for a controller to be "started," and how is that different than "resumed?" What is the distinction between "paused" and "stopped?" These state names do not convey the nuance and complexity that they encompass. Notice that the docs have parentheses explaining how these controller states match to the view life cycle, which is the more natural way to understand when these hooks will be called. Furthermore, by using the terminology "onEvent," Android fails to communicate whether system level events tied to that event come before or after the hook. For instance, when a controller is paused, is the hook called immediately while the view is still on screen, or after the view has been partially occluded? This ambiguous naming increases learning time and adds cognitive overhead.

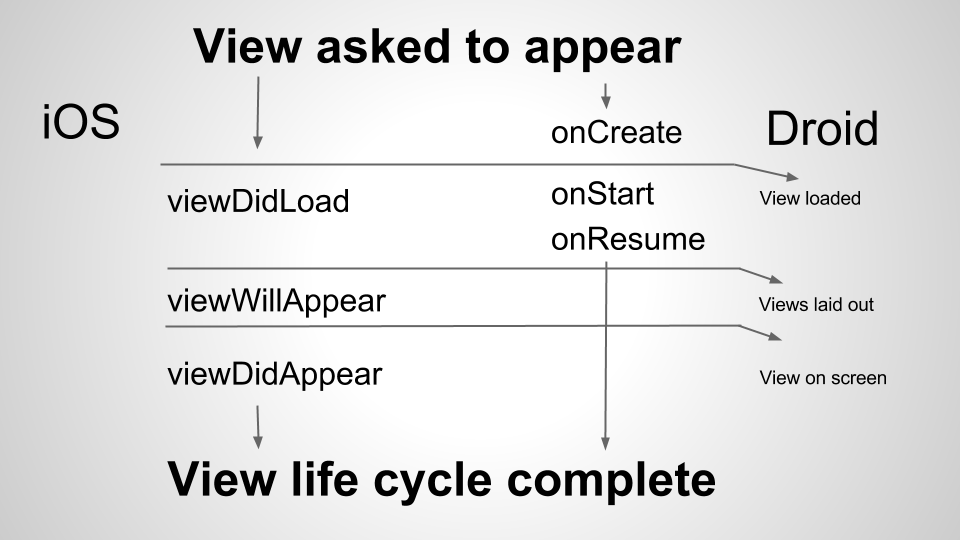

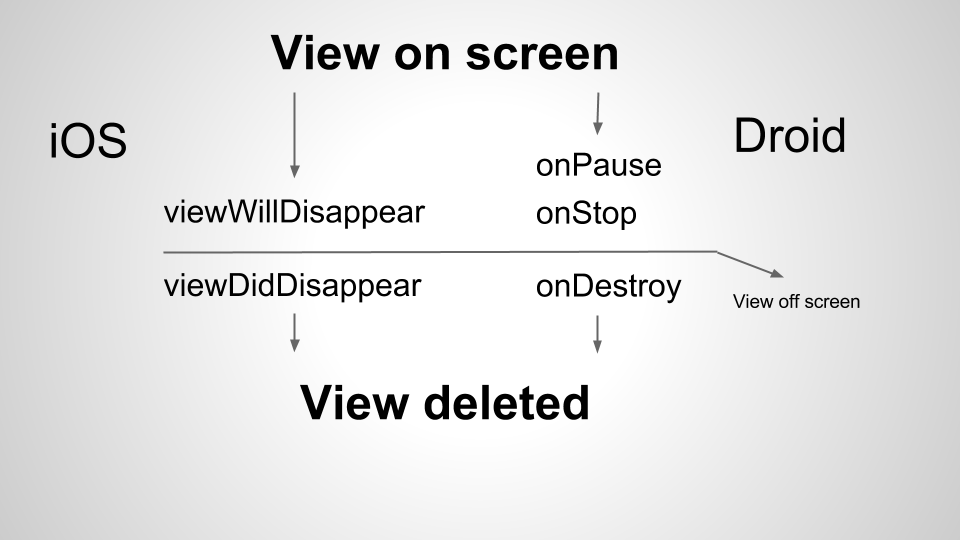

Here's a quick comparison of the most common lifecycle methods on the two platforms, and where they fit into the life cycle of the view.

Side by side, the difference between iOS's view abstraction and Android's controller abstraction becomes apparent. Apple has one hook at each stage, but Android sometimes has multiple hooks, or no hooks at all. In other words, Android's controller abstraction doesn't match what a developer needs to do, making the system difficult to understand, and making it difficult to figure out where code should go.

Furthermore, by abstracting on the controller events, Android has tightly coupled the view's life cycle with the controller's life cycle, breaking the fundamental abstraction of MVC. For instance, on screen rotation, Android envisioned a scenario where a developer would want to substitute different layouts for landscape and portrait modes. This is a noble goal, and I applaud the flexibility that it grants. However, due to the controller abstraction, in order to change the view, the controller also needs to change. In other words, to swap out the view and call all of the life cycle hooks again, the entire controller needs to be destroyed and recreated, along with all of its data and state. If the controller is not recreated properly, the resulting view could have bugs, lose data, or even crash, even though nothing in the controller has changed. Thus, by abstracting on the controller, Android has complected the view and the controller, which breaks the basic abstraction of MVC. It's an absolutely terrible design. As if that's not bad enough, saving and recreating a view can be heinously difficult, which I will cover in a separate blog post.

Rotation is not an isolated case; Android's controller abstraction leaks controller concerns and system level complexity into the realm of the developer anywhere and everywhere. Here's a partial list of other life cycle quirks and gotchas that await the unwary Android developer.

- Backgrounded apps brought to the foreground will often crash if state is not persisted properly.

- The developer has to be aware that the system can destroy activities in the background.

- onSaveInstanceState is not always called, such as when the user “intentionally” exits the app.

- The developer has to manually cache the state of the controller.

- Persisted controllers can have data split between a bundle and a permanent store.

- There are often multiple ways that a hook can be called, and the developer needs to be aware of the differences in certain situations.

- There are quirks with older versions of Android, notably that

onStopis not guaranteed to be called in early versions of Android. - Google maps objects have their own separate hell of a life cycle.

Some of these points represent major failures of design, while others "merely" add complexity. While discussing these issues is beyond the scope of this post, if there's anything in particular you would like to read more about, drop me a comment and I'll do my best to put together a post on that subject.

In contrast to Android, by tying hooks to the view, iOS has found the correct abstraction. The hooks only assert that the view did appear, or the view will disappear. There is no mention of, and really no room for, a concept of why these events might have happened. Thus, the view abstraction requires that much of the controller complexity be handled in the background. Complexity around whether a view should be cached, whether the system needs to reclaim memory from the controller, etc, CANNOT leak out into the realm of the developer. It's a fantastic separation of concerns, enforced by design.

To sum up, when I learned iOS, I coded for months with only the barest appreciation for what was being handled for me behind the scenes. I had no idea what the system was doing to my views and controllers when the app was backgrounded, or when the phone was rotated. And I didn't care, I put my code in the logical life cycle hook, and it just worked. On the other hand, by requiring the developer to be aware of the controller's state, Android has introduced a massive amount of incidental complexity. Eight months into the development of my first Android app, I was still encountering issues, edge cases, and crashes pertaining to lifecycle. I was still referring to documentation, and discovering new, important details about how the system worked. Overall, Android's handling of life cycle feels poorly designed, and poorly executed. In fairness to the framework engineers, Java imposes limitations, and I'm sure there are many other constraints that I'm not aware of that pushed the design in this direction. But, with iOS as an example, I would like to see reductions in the complexity of view and controller life cycle in future versions of Android.